From WebExtension to Electron in one (build) step

Written by Jeroen van Veen on 17th October 2017

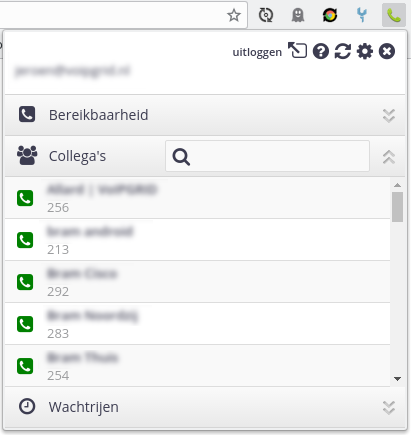

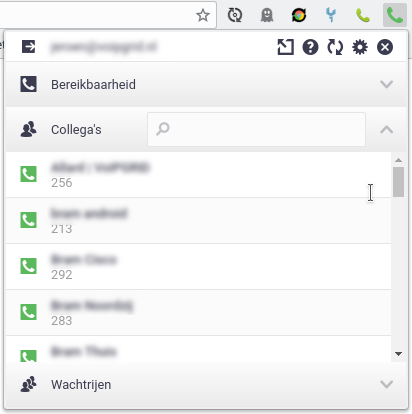

At Spindle, we develop and maintain an opensource browser plugin. Customers of the VoIPGRID platform find it a useful tool to make calls directly from the browser. It allows them to update their availability, to manage calling queues and to use the colleagues list as a Busy Lamp Field (BLF). Currently, there is a browser plugin for Firefox and for Chrome. Each of the plugins has its own repository, similar dependencies, and codebase.

Refactoring Click-to-dial

In November 2017, Mozilla plans to abandon its legacy Addon SDK with the release of Firefox 57. The legacy API is being replaced by the WebExtensions API, which is a plugin standard that multiple browser vendors adhered to.

This decision affects our legacy Firefox plugin, so we already started in April with refactoring the plugin code. This was also a good opportunity for us to lift the codebase to today’s standards. Tools like Gulp, NPM package management, CSS preprocessing, and Browserify module bundling make development faster, less error-prone and more enjoyable for developers and end-users.

Focus on maintainability

We first decided to use a single repository for both Firefox and Chrome and started with the current Chrome plugin as a reference. The reason for this is that Firefox already supports the Chrome-specific plugin code, so we wouldn’t have to change the method calls to make the code work in both Chrome and Firefox. We are not exactly using the WebExtension API code (yet). The WebExtension standard uses Promise-style API methods, which Chrome doesn’t support yet without a webextension polyfill.

A build tool (Gulp) was introduced, and the code was rewritten to CommonJS modules. Browserify tasks were added to gather code from several script entry points during build time. We moved code around to fit into more logical modules and added some environmental flags to distinguish between plugin script types. Introducing modules brought structuring to our code and allowed us to remove a lot of globals that were required when the code was still scattered across several included scripts.

The plugin API EventEmitter

Most of the browser plugin-specific Javascript code were calls to chrome.runtime.sendMessage and chrome.runtime.onMessage. A plugin can emit and listen for events, just like a typical EventEmitter in Node.js and browser applications. The major difference is that the plugin API is able to communicate between several running plugin scripts. Our plugin involves quite some scripts:

- Background script – Started when the browser is started. Responsible for handling API calls, updating SIP presence information, keeping state in sync with local storage and informing other scripts about state. It is the script that is responsible for maintaining data and informing other scripts about it.

- Popup script – Started each time a user clicks the click-to-dial icon in the Chrome/Firefox menu. It shows the main UI of the plugin. It also handles incoming GUI events and sends events to the background about what the user intends to do.

- Popout script – Basically a copy of the popup script, but running in a browser tab instead of the browser’s menu popup. It has some peculiarities that make it act a bit different than the popup version. The popout is opened with a query string in the URL to identify it as a popout, so its behavior can deviate from the popup.

- Tab script – Running in each browser tab. It is responsible for injecting a callstatus dialog into the page on request and acts as a bridge between the callstatus script and the background script, passing messages about the current callstatus between the two.

- Callstatus script – Injected in the current tab by the tab script as soon as the user clicks on a click-to-dial icon next to a phonenumber or uses the context menu on a phonenumber.

- Observer script – Responsible for identifying phonenumbers within a frame on a page and injecting call icons next to each of them.

- Options script – Settings page for the browser plugin.

To make the plugin less dependent on plugin API calls, I replaced all calls to chrome.runtime.sendMessage and chrome.runtime.onMessage with a regular Node-style inherited EventEmitter. The plugin’s API-specific code is now moved back to the EventEmitter’s .on and .emit methods. The new EventEmitter can switch between acting as an IPC EventEmitter (which sends messages across scripts) and a regular EventEmitter while keeping the same syntax. Besides making Event handling look more familiar and easier to maintain, it also enables switching to a single script mode where only local event emitting occurs. This version runs in a single browser page/webview.

Time for some polishing

We structured and cleaned up all hardcoded CSS by using a CSS preprocessor (SASS). HTML files, CSS classes and redundant assets were cleaned up. A new icon set was created, new assets designed and the current styling was nested properly, removing styling inconsistencies where we encountered them. Some partners forked the original repository in the past, to make their own branded version of the plugin. This is not necessary anymore. All user-facing hardcoded references to the plugin can now be supplied at build time (branding colors/domains, naming, store preferences, etc.), making it much easier for anyone who wants to maintain and release a branded version of the plugin.

What did we achieve?

The refactoring process was mainly focussed on restructuring existing code and adding an enhanced build process. But what did we gain? The plugin’s functionality is after all almost the same as before with just some minor adjustments and fixes.

First of all, we succeeded in accomplishing the main goal, which is that the updated plugin would still be working in Firefox after the release of Firefox 57.

Besides the main goal, the refactored plugin now also allows us to develop new functionality at a much faster pace than before. The plugin is automatically rebuilt when a file changes, and we can use a regular browser page with live reload to develop most of the functionality and styling, which results in quicker development cycles. The build process automates and standardizes most of the tedious tasks like rebuilding the plugin after a change, generating browser-specific manifest-files, creating a (distribution) build, managing third-party assets from npm, updating GitHub documentation pages and deployment to the Firefox and Chrome store.

We can now also consider targeting new WebExtension-compatible browsers like Microsoft Edge, given that Microsoft claims that Edge supports (most of) the web-extensions API.

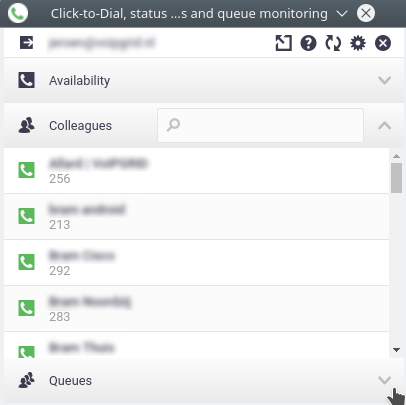

Experiment with Electron

An interesting side-effect of being able to run all code in a single script environment is that we gained a potential new build target: Electron. The core functionality of the Click-to-dial plugin runs without issues as an Electron desktop application in a webview container. Notifications are working fine, but of course you will be missing the Click-to-dial icons that are placed in a browser’s tab pages.

This is just a proof-of-concept. There is an experimental Electron build if you would like to check it out. Having a desktop version of the plugin available could prove useful as soon we start integrating it with WebRTC-based calling features.

What is next?

There has been a lot of progress lately by our infra-team, working on WebRTC-enabled calling via the VoIPGRID platform. Click-to-dial can use this upcoming WebRTC-enabled stack to receive and make calls with. It basically means calling support within the plugin, via the desktop version of the plugin or from a web page running the plugin. It eliminates the need for a hardphone or a regular desktop softphone in most situations.

We are also currently in the (early) process of designing and implementing a new frontend for the VoIPGRID portal. The (concept) design for the new portal has the Click-to-dial plugin integrated as a component in the portal. Having a webview compatible build available makes this an option as well.

I think in the long run, we should keep focussing on improving the plugin’s code quality by replacing all manual DOM manipulation (Jquery) with a virtual DOM and use a Node.js compatible SIP-library (Sip.js). Then we will be able to make the plugin completely browser-agnostic. Running it in Node.js gives a lot of opportunities for writing automated tests. Also, we could think of adding a programmatic API to the plugin, so developers can use it to create their own serverside VoIPGRID services using Node.js. Time will tell. I hope this article gives you an idea of how we were able to refactor this plugin. See the project’s GitHub page if you would like to see some technical details.

Your thoughts

No comments so far